- University of Texas School of Law, Austin, TX, United States

What years of deterrence efforts and restrictions on asylum did not achieve to block the U.S. southern border to asylum seekers, the Trump Administration has now accomplished using the COVID-19 pandemic as justification. New measures exclude asylum seekers from U.S. territory, thereby effectively obliterating the U.S. asylum program, which had promised refugee protection in the form of asylum to eligible migrants who reach the United States. In some cases, the policies adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic harden impediments to asylum already in place or implement restrictions that had been proposed but could only now be adopted. In others, the policies could never have been imagined before the pandemic. Overall, the force of these measures in dismantling the asylum system cannot be overemphasized. Once adopted, using an emergency rationale based on the pandemic, these policies are likely to become extremely difficult to reverse. This is particularly true where the restrictions exclude asylum seekers from the physical space of the United States. This article will thus explore two modes of physical exclusion taking place at the U.S. southern border during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) indefinitely trapping in Mexico those asylum seekers who are subject to the so-called Migrant Protection Protocols; and (2) immediate expulsions of asylum seekers arriving at the southern border pursuant to purported public health guidance issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Introduction

What years of deterrence efforts and restrictions on asylum did not achieve to block the U.S. southern border to asylum seekers, the Trump Administration has now accomplished using the COVID-19 pandemic as justification. New measures exclude asylum seekers from U.S. territory, thereby effectively obliterating the U.S. asylum program and its promise of refugee protection for eligible migrants who reach the United States.1

In some cases, policies adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic harden impediments to accessing asylum that were already in place or implement restrictions that had been previously proposed but could only now be adopted. In others, the policies could never have been imagined before the pandemic. Overall, the force of these measures in dismantling the asylum system cannot be overemphasized. Once adopted, using an emergency rationale based on the pandemic, these policies are likely to become extremely difficult to reverse.

Restrictions that exclude asylum seekers from the territory of the United States are especially likely to become permanent fixtures of the system. This article will thus explore two modes of territorial exclusion taking place at the U.S. southern border during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) indefinitely trapping in Mexico those asylum seekers who are subject to the so-called Migrant Protection Protocols; and (2) immediate expulsions of asylum seekers arriving at the southern border pursuant to purported public health guidance issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The article also asks how the territorial exclusion of asylum seekers ever occurred and examines the underlying exclusionary logic of the U.S. asylum system. It emphasizes the importance not only of dismantling the border blockade but also of forging a new path forward toward protection rather than exclusion.

Before COVID-19—Escalating Exclusion Efforts

For years, the United States has sought to deter, or flatly prevent, migrants from accessing the asylum system available to those who reach U.S. territory. The United States has deployed a broad range of “remote control” measures to keep asylum seekers at bay, far removed from the physical border of the United States, with limited success (Fitzgerald, 2019). These measures include, for example, visa and passenger carrier controls abroad but also encouragement of other countries to deport migrants back to their home countries long before they reach the United States (Fitzgerald, 2019). While these efforts may have occasionally slowed the flow of asylum seekers toward the United States, significant numbers still reach the U.S. southern border.2

Similarly, the United States has attempted to deter arrivals by making the U.S. asylum system harsher, with little impact on the numbers of asylum seekers reaching the border, although with significant negative impact on asylum seekers themselves. These efforts have escalated under the Trump Administration and included even the separation of young children from their parents.3 They have also included expanded prolonged detention of asylum seekers, including entire families,4 even during the COVID-19 epidemic (Eagly and Shafer, 2020). Additional policies include the so-called “transit ban,” which bars asylum eligibility for those who transited through Mexico or any other party to the UN Refugee Convention without applying for asylum and receiving a negative decision.5 The ban has now been declared unlawful and its application halted, but only after resulting in the denial of numerous viable asylum claims.6 The actions intended to deter and thus exclude asylum seekers also encompass new restrictive interpretations of substantive asylum law, which make it difficult if not impossible for many asylum seekers to achieve protection. The Attorney General's decision in Matter of A-B7 is one such interpretation, which largely precludes claims based on domestic violence and gang violence.

These deterrence efforts have had no meaningful impact on the arrivals of new asylum seekers at the southern border. Empirical research finds that migrants are driven by violence in the home region and are not deterred by knowledge of heightened U.S. enforcement efforts.8 Data regarding arrival of asylum-seeking families further establishes the point. Thus, for example, since the inception of widescale family detention in 2014 and even in the wake of the 2018 family separation policies that sought to deter Central American asylum seeking families, the numbers of families arriving at the southern border increased, albeit with some fluctuations.9

Given these failures in limiting arrivals of asylum seekers at the southern U.S. border through remote control and deterrence measures, the United States took a different tack. The United States has turned to measures implemented at the border to block asylum seekers from accessing U.S. territory and the U.S. asylum system.

These territorial exclusion measures became increasingly aggressive after the inauguration of President Trump, even before the outbreak of COVID-19. Initially, the Trump Administration expanded and institutionalized a practice whereby asylum seekers arriving at official ports of entry on the U.S. southern border were turned away with an assertion that the U.S. was “full” and could not process more asylum seekers10. Under this practice, sometimes known as “metering,” asylum seekers were required to place their names on waitlists in order to cross into the United States and to be processed into asylum proceedings in the United States.

Then, beginning in January 2019, the Trump Administration implemented the Migrant Protection Protocols (“MPP”), a program pursuant to which individuals placed in U.S. asylum proceedings at the southern border were physically returned to Mexico to await asylum proceedings in U.S. immigration courts.11 This program will be further described below, as it has led to hardened exclusion at the border during COVID-19.

Later in 2019, the Trump Administration entered agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to send asylum seekers arriving at the U.S. southern border to those three Central American countries to seek asylum there rather than in the United States.12 The agreements envisioned sending asylum seekers from the U.S. southern border to the Central American countries, all three of which have high levels of violence and underdeveloped asylum systems, without requiring any connection between the asylum seekers and the country that would be processing their claims.13 Almost one thousand asylum seekers were transferred from the U.S. southern border to Guatemala under the agreement with that country.14 Such transfers would likely have become even more commonplace to all three countries if it were not for the outbreak of COVID-19 and the refusals of countries to accept their non-nationals15.

COVID-19—Blocking the Border

This is the backdrop of escalating border blockage that was in place when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The Trump Administration then hardened territorial exclusion measures to erect a barricade at the border for asylum seekers. This barricade upended the U.S. asylum system, which provides for the possibility of asylum for any migrant “who is physically present in the United States or who arrives in the United States (whether or not at a designated port of arrival” and meets the refugee definition.”16 While arrival at the U.S. border and entry into the country were still physically possible,17 prompt ejection from the territory of the United States became the rule. It thus became effectively impossible to be “present” on U.S. territory and to enter the U.S. asylum system.

The best measure of new asylum seekers processed in the United States—referrals for credible fear screening interviews—demonstrates the dramatic nature of the exclusion. Referrals dropped from over 5000 in July 2019 to fewer than 350 in July 2020.18 From February 2020 to April 2020, the number dropped from over 2,000 to under 450.19

The territorial exclusion measures at the southern border operate in conjunction with other policies predating the pandemic described above, not all of which involve a border blockade but which nonetheless make it exceedingly difficult to secure asylum protection in the United States. And the Trump administration has continued to expand policies that leave asylum seekers largely beyond the reach of the law during the time of COVID-19, even when they do make their way onto U.S. territory. Most recently, for example, the Trump administration has relied on the COVID-19 outbreak to propose a new rule that certain asylum seekers, who have symptoms of a communicable disease or who simply have originated in or transited through a region with an outbreak of communicable disease, are ineligible for refugee protection on national security grounds.20 If adopted as a final rule, this novel interpretation of the national security bar to asylum would prevent many legitimate refugees from obtaining asylum based merely on their country of origin or transit.

Yet, it is crucial to distinguish between those actions that serve to limit access to protection under the legal framework for asylum and those actions that territorially exclude asylum seekers arriving at the southern border before or in place of adjudication of their asylum claims. The transit ban or the proposed new contagion bar to asylum might at first glance appear to effectuate territorial exclusion, but they are actually limits on eligibility for refugee protection as a substantive law matter. The distinction is between policies that make it exceedingly difficult to win asylum and remain in the United States and policies that prevent an asylum seeker from accessing U.S. territory and the asylum process in the first place in order to plead for protection from within this country. The distinction is critical, because the territorial exclusion policies have had a uniquely sweeping impact denying asylum seekers any opportunity for protection in the United States. In addition, as discussed below, it will likely be significantly more challenging to end policies of territorial exclusion. Further discussion follows, then, of the two main territorial barricades in place during the time of COVID-19—the Migrant Protection Protocols and expulsions under order of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.21

Migrant Protection Protocols—Trapping Asylum Seekers in Danger in Mexico

Beginning in early 2019, the Migrant Protection Protocols (“MPP”), otherwise known as the “Remain in Mexico” program, trapped asylum seekers physically in Mexico while their asylum claims moved forward slowly in border immigration courts inside the United States.22 Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the exclusion from the United States executed through MPP has become indefinite if not permanent as all hearings in MPP cases have been suspended.

Under the MPP program, asylum seekers who arrive in or enter the United States from Mexico may be sent back to Mexico for the duration of their U.S. immigration proceedings. The program was initially rolled out in San Diego, California, followed by implementation in El Paso, Texas and then the south Texas border.23 The program originally applied only to migrants from Spanish-speaking countries, although it was eventually extended to include nationals of Brazil.24 On its face, the program targeted families with children, particularly from Central America. In explaining the program, officials stated:

Historically, illegal aliens to the U.S. were predominantly single adult males from Mexico now over 60% are family units and unaccompanied children and 60% are non-Mexican. In FY17, CBP apprehended 94,285 family units from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador (Northern Triangle) at the Southern border25.

Implementing MPP required the U.S. government to seek the involvement of the Mexican government, because Mexico is the country to which the asylum seekers are sent while they await their U.S. asylum proceedings. The United States threatened tariffs and damage to bilateral relations to force Mexico to join in implementing MPP.26 Mexico acquiesced to U.S. demands and participated in the program by accepting asylum seekers back into Mexico after exclusion from U.S. territory. While Mexico thus is complicit in U.S. actions denying access to U.S. territory and the asylum process, the United States also is responsible for coercing Mexico to take on this role.

The MPP program is based on a provision in U.S. immigration law, which allows certain migrants arriving by land “from a foreign country contiguous to the United States” to be returned to that territory pending immigration proceedings.27 There are strong legal arguments under U.S. law suggesting that the provision may not be used against asylum seekers, and it had never before been used to return asylum seekers to Mexico until the MPP rollout in 2019.28

Nonetheless, as of March, 2020, the U.S. had sent nearly 65,000 migrants back to Mexico to await their U.S. asylum proceedings under the MPP program.29 Those asylum seekers subject to the program suffered an effective denial of access to the United States and the possibility of asylum protection even before the pandemic, and their situation has become even more dire since the outbreak of COVID-19.

Many in MPP have suffered extreme violence in Mexico. As of May 2020, there were more than 1,000 documented cases of murder, rape and other assaults impacting asylum seekers in Mexico under MPP.30 Asylum seekers also face grave health threats. Medical professionals have documented the reality that migrants trapped in northern Mexico are “subject to a gamut of communicable and non-communicable diseases” and inadequate health services are available to them.31 Many asylum seekers in Mexico live in camps and shelters lacking in infrastructure, which have become tinderboxes for outbreaks of COVID-19.32

The risk of violence or other harm leads some asylum seekers to give up their claims, placing them in grave danger upon return to their home countries.33 Furthermore, Mexican authorities have coerced asylum seekers to board buses taking them south without any means of returning to the border for hearings, which also leads to abandonment of asylum claims and return to potential persecution in home countries.

Asylum seekers forced to wait in Mexico for their hearings in the U.S. border immigration courts faced denials of basic due process even before the pandemic shut down the courts. Unsurprisingly, success rates in MPP were miniscule—only about 1% of individuals receiving a final decision were granted asylum or related protection as of March 2020.34

Asylum seekers in MPP were required to present at the U.S. border on multiple occasions and often at 4:30 am, to attend their hearings. They were not permitted to travel to the court on their own or with counsel but instead were escorted by immigration officials and were confined strictly within the court complex.35 In Laredo and Brownsville, Texas, the courts hearing MPP cases are temporary facilities within the border port of entry where hearings were conducted by video with immigration judges sitting elsewhere.

Because the asylum seekers in MPP were forced to live in Mexico between hearings, most faced extreme difficulties in securing counsel or communicating with the few attorneys who agreed to take MPP cases. It was almost impossible for asylum seekers to prepare and present an asylum case in this context. Layered on top of these limitations, asylum seekers in MPP also had to overcome the other restrictions on asylum imposed in recent years, including the caselaw limiting domestic violence and gang claims. Because the probability of achieving protection through asylum in MPP proceedings is so low, after being returned to Mexico, most asylum seekers in MPP were never allowed to enter the United States, other than for day-long escorted visits to attend hearings at the border.

Those MPP realities of exclusion are now overshadowed by the indefinite and possibly permanent physical exclusion of asylum seekers in MPP because of the suspension of hearings. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, all hearings in MPP cases have been suspended, and no date has been set for their resumption. The MPP hearings were initially suspended for definite time periods through June 19, 2020, in a series of announcements issued on March 23, April 1, and May 10, 2020.36 Then, in an announcement on July 17, 2020, the suspension of hearings was extended indefinitely.37 The latest announcement provides for a resumption of hearings only when the dangers of the COVID-19 pandemic have been determined by the U.S. government to have diminished.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government continues to place asylum seekers into MPP and return them to Mexico knowing full well that their proceedings in the border immigration courts will not move forward. Their placement in the program is simply expulsion to Mexico with a misleading claim that asylum proceedings will take place in the United States.38

As a result of the suspension of hearings, as of the fall of 2020, asylum seekers have already been blocked from accessing the United States for well over six months. They will likely be barred for at least months or years into the future. During this time of suspended hearings, asylum seekers are no longer presenting at the border at all so that they have no contact with the U.S. asylum system and no possibility for adjudication of their claims. Thus, even those who would qualify for asylum under current restrictive policies have no opportunity in the foreseeable future to gain asylum and then to enter the United States.39 They are blockaded at the entry point to the United States.

With the suspended hearings and no foreseeable possibility of entering the United States, many asylum seekers will abandon their efforts to seek protection. It is not an exaggeration to say that many others will likely succumb to fatal illness or murder.40 For many asylum seekers, then, physical exclusion from the United States will become permanent without any opportunity for a determination on the asylum claim.

CDC Entry Ban—Immediate Expulsions of Asylum Seekers at the Border

Most recently, as MPP exclusions continued to play out, the Trump Administration invoked the COVID-19 pandemic to halt all entry into U.S. territory by asylum seekers through orders of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.41 The CDC orders provide for the immediate expulsion of asylum seekers arriving at U.S. land borders without permitting access to the asylum process or any other immigration process.42

The CDC first issued a temporary order in March 2020 prohibiting entry into the United States of non-citizens arriving at a U.S. land border with exceptions. In May 2020, the CDC made indefinite the prohibition on entry for certain non-citizens, extending the ban until COVID-19 “cease[s] to be a serious danger to the public health.”43 The indefinite ban includes individuals arriving to land or coastal borders.

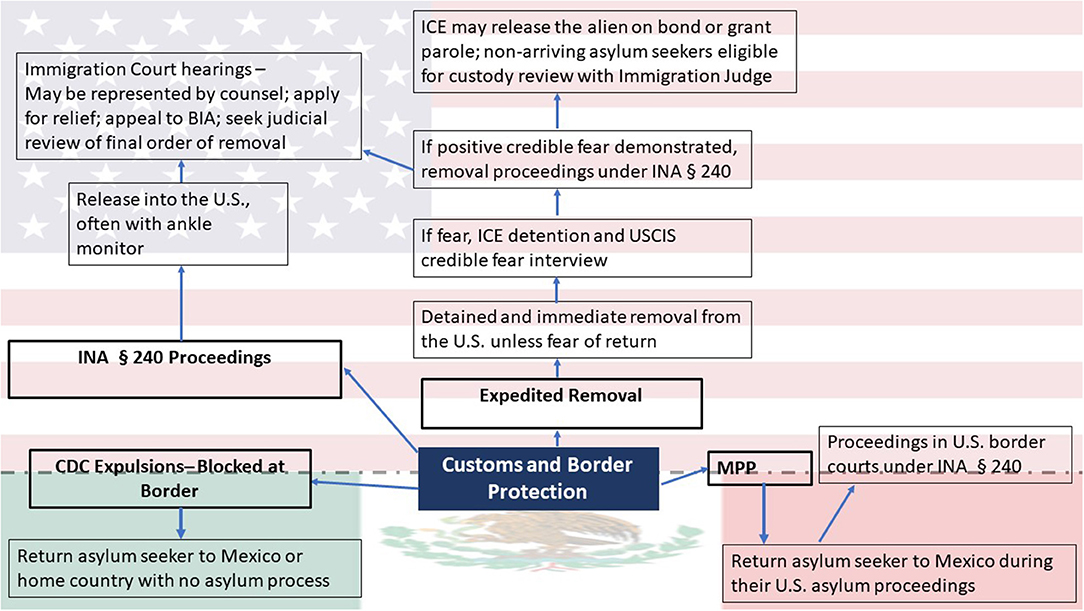

The CDC expulsions supersede the normal processes applicable to asylum seekers. Normal procedures for adult asylum seekers and families would require: (1) placement in removal proceedings within the United States where the asylum claim would be heard; (2) placement in expedited removal proceedings within the United States with the possibility of entering full removal proceedings where the asylum claim would be heard; or (3) placement in MPP with removal to Mexico but with the initiation of U.S. removal proceedings.44 For unaccompanied children, applicable procedures would generally prevent their immediate expulsion and instead require placement in asylum proceedings.45 CDC expulsions follow none of these procedures. The CDC orders thus block asylum seekers from access to U.S. territory in a way that also completely avoids the asylum proceeding that would otherwise be provided, See Figure 1.

Migrants expelled under the CDC orders have been returned either to the country from which they arrived, mainly Mexico, or to their countries of origin. As with the MPP program, Mexico has allowed implementation of the orders by accepting migrants back on to Mexican territory and otherwise offering full support for border measures adopted by the United States during the pandemic.46 Under pressure from the United States, other countries are also accepting their nationals back after expulsion at the U.S. southern border47.

The expulsions have blocked more than 200,000 migrants at the U.S. southern border, many of whom likely intended to seek asylum.48 Among those expelled at the border are more than 8,000 unaccompanied children.49 These children are processed briefly, often in settings such as hotels that are not appropriate for the care of children, and then returned to Mexico or to their country of origin without any consideration of their protection needs.50

The CDC orders purport to be motivated by public health concerns but are instead specifically designed to exclude asylum seekers from the United States. The orders did not originate with the CDC but rather with the Trump administration leadership, which has been focused on exclusion of asylum seekers as described above.51

Meanwhile, other countries, including 20 countries in Europe, adopted travel restrictions at international borders and other precautions to address the COVID-19 crisis but specifically excepted asylum seekers from border closures or entry bans.52 The United States took the opposite approach, demonstrating the focus on asylum exclusion.

A particular focus on excluding asylum seekers is evident in the language of the CDC orders that justify immediate expulsions on the grounds that those affected would otherwise be “held for significant periods of time in [border] facilities” for processing53. Those who are held for longer periods are those who must be referred into further proceedings under the asylum rules. Migrants who are simply turned away at the border as inadmissible, without making an asylum claim, do not require any more processing under existing rules than is required to process them for expulsion under the CDC orders. The original CDC order also specifically mentioned “asylum camps and shelters” in Mexico and the risk of contagion there as part of the justification for blocking entrants from Mexico.54

The CDC orders are also both under and overinclusive in ways that make clear that the focus is on achieving territorial exclusion of asylum seekers at the border at all costs, without regard to public health considerations. The CDC expulsions have never included U.S. citizens, Lawful Permanent Residents, visa holders or airport arrivals, and separate guidance has allowed for continued entry into the U.S. for commerce and education purposes.55 So the directive only impacts individuals arriving at the border who do not have existing immigration status and would require extensive processing in border facilities. The group covered under these criteria is almost entirely the category of asylum seekers.

The ban is thus underinclusive if the concern is really directed at the entry of individuals who might be infected with COVID-19 and who might spread the disease within the United States since there is no indication that asylum seekers or others without status would be more likely to be contagious than those exempted from the CDC orders. On the other hand, the ban is overinclusive. It incorrectly assumes categorically that those arriving at the border would be likely to be contagious and could not be handled by means other than exclusion, on the theory that they would not have the possibility of quarantining effectively within the United States. The orders require no individualized inquiry into the realities of the situation in individual cases and no testing or other screenings to determine which asylum seekers are infected or present a risk. In the cases of unaccompanied children, as a practical matter, the ban only applies to those children who test negatively for corona virus, since the countries of origin will not accept returned children who test positive.56 It thus covers and excludes those who present the least serious health risk.

The expulsions thus impact a broad category of migrants—asylum seekers—in a manner that ensnares many who do not present the problem purportedly to be addressed. The mismatch between justification and impacted migrants lays bare the ban's anti-asylum foundation.

There is also little, if any, evidence that the CDC expulsions function effectively to protect public health. International guidelines discourage travel restrictions on the grounds that “restricting the movement of people and goods during public health emergencies is ineffective in most situations and may divert resources from other interventions.”57 The CDC's own scientists questioned the public health basis for the ban.58 Independent medical experts also questioned the wisdom of the ban and offered measures that could be taken without banning asylum seekers, which would offer more tailored protection against the introduction of additional contagion risk into the country.59 The failure to adopt these alternatives further highlights the extent to which the ban is intended to exclude asylum seekers.

In addition, the CDC expulsions do not even ensure rapid processing, although the purported purpose is to ensure that migrants do not remain in the custody of U.S. border officials for extended periods in order to avoid contagion. There would be more effective ways to ensure prompt processing out of border facilities, including immediate release to families within the United States.

Instead, the CDC expulsions turn away hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers at the border, including young children on their own, and send them to danger in Mexico or their home countries. This exclusion of asylum seekers is not a side effect of a valid public health measure; it is the intended result.

The Need to Avoid a Permanent Border Blockade

While these measures of territorial exclusion at the border have been put in place in reliance on the dangers posed by a pandemic, the real danger is that the border blockade will become permanent. The success of the exclusion measures in closing the border and placing asylum seekers just out of reach of U.S. territory makes it challenging to rebuild a meaningful pathway to asylum at the southern U.S. border.

The impacted asylum seekers reached U.S. territory and so should have enjoyed the legal rights that accompany such arrival,60 but the barricade at the border pushed them back just enough to make full enforcement of those rights a challenge. Several U.S. courts have issued decisions finding the MPP and CDC exclusion measures to be in likely violation of law.61 Nonetheless, they have allowed for implementation of MPP returns to Mexico and the CDC expulsions while the legality questions are litigated.62 The courts appear to struggle with the unique issues raised by migrants at the border, right at the edge of the United States.63 The court decisions suggest a restrained approach in assessing border policies, but rather than allowing for restraint, they have allowed the Trump Administration to reshape the law dramatically to block asylum seekers at the border. Now that the exclusionary programs have been allowed to take effect, invalidation would require a remedy for the hundreds of thousands of migrants who have already been turned away at the border. The courts may thus be less likely than ever to end the exclusionary policies.

Similarly, at the international level, international refugee and human rights bodies have insisted that migrants arriving at an international border, like the U.S. southern border, have the right to access asylum and non-refoulement protections (the right not to be returned to a country where they will face persecution or torture), even in the context of the pandemic. While not concretely addressing the measures adopted by the United States, UNHCR has stated that the right to asylum and non-refoulement applies, “including at national frontiers.”64 The refugee agency went on to assert that States are prohibited from “denying entry or forcibly removing” protection seekers. Other United Nations bodies have also insisted that “States must ensure the continuity of asylum at the borders” during the pandemic.65 The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has specifically expressed concern about the impact on the right to seek asylum caused by the actions of the United States in implementing both MPP and the CDC expulsions.66

Yet, international bodies have not taken active measures to pressure the United States to rescind the border blockade against asylum seekers. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which is the only body that can accept individual complaints against the United States, recently declined to grant a request for precautionary measures seeking to end the MPP program.67 Like U.S. courts, the international bodies may be reticent to act, because the law on migrants' rights at the border is not as fully developed or as protective as in other realms.68 The unique circumstances involving potential human rights violations by multiple States at once may also be contributing to inaction by international bodies. Regardless of the reasons, the United States has proceeded with its border blockade without any meaningful resistance from the international community.

Just as legal challenges under international and domestic law have so far fallen short in halting the border blockade, change will be difficult as a policy matter as well. The border exclusions function to place asylum seekers outside of the sights of policymakers and the public. It will require intensive efforts to have any Administration view the absence of asylum seekers entering the U.S. system at the southern border as a serious concern that must be addressed. Without clear instruction and accountability at the top, it is unlikely that U.S. officials will reopen the border to asylum seekers. U.S. border agencies are notoriously resistant to changes in general, particularly those that might require more humane treatment of asylum seekers.69 They are unlikely to readily abandon the MPP and CDC expulsions programs that are now fully functioning to turn away hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers quickly and easily.

However, urgent intervention is exactly what is needed to avoid the conversion of the territorial exclusion policies into a permanent fixture. The longer the MPP and CDC Orders continue to function to block the border, the more unmovable the blockade will become. With each day, more asylum seekers are pushed out of reach of the asylum process and out of easy range of the mechanisms that could reopen the border for them to seek protection. As the problem grows, the solutions become more difficult, creating a real intractability problem. Invalidation of the programs is required as soon as possible to restore access to asylum and the rule of law at the U.S. southern border.

To achieve this result, further inquiry will also be required to understand how the United States arrived at this juncture in the first place. There can be no doubt that the restrictionist tendencies of the Trump Administration combined with the pandemic allowed the blockade in the immediate sense.

However, it seems likely that the security and border control logic of the U.S. asylum system created the opportunity for such a shift toward full territorial exclusion to occur. Based on a logic of threat control, the U.S. asylum system has long prioritized excluding asylum seekers as dangerous or perfidious rather than on processing and deciding claims for protection. Removal thus becomes the presumptive approach of the system and a grant of asylum protection the rare exception.

The language utilized by the Trump Administration in implementing border exclusion policies makes clear that these actions find a foundation in a system that focuses on concerns about fraud and security rather than effective or efficient adjudication. For example, in announcing MPP, the program was described as a tool to be utilized against asylum seekers in order to address “false claims to stay in the U.S.”70 The CDC expulsions also treat asylum seekers as a threat by claiming that they prejudice public health.

The exclusionary approach of the U.S. asylum system has a long history that extends even further back than the remote control and deterrence efforts that led up to the border blockade established under the Trump administration and solidified with COVID-19. In fact, recent measures of territorial exclusion find their closest parallel in pivotal historic moments when the U.S. blocked the entry of asylum seekers pleading for protection. The most shameful historic precursor to the current blockade is the 1939 refusal of the United States to allow the disembarkment on U.S. territory of Jewish refugees arriving near the Florida coast on the St. Louis German ship.71 The St. Louis carried 937 passengers, almost all Jews fleeing the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany. After the passengers were refused any opportunity to enter and seek protection in the United States, the ship returned to Europe. In the end, 254 St. Louis passengers were killed in the Holocaust. The exclusion of individuals fleeing Europe during World War II was based in part on claims by U.S. leadership that the refugees presented a national security threat including by spying for Germany.72

In the wake of World War II, the United States purported to commit itself to protecting those fleeing persecution so that another St. Louis would not occur (Goodman, 2016). The United States ratified the international refugee treaty and eventually adopted domestic legislation to create an asylum program.73 Yet, before the ink was even dry on U.S. asylum law, the United States began to turn away Cuban and Haitian asylum seekers fleeing autocratic regimes and approaching our shores to seek protection.74 Territorial exclusion prevented most from having their asylum claims heard. This is the historical backdrop of the U.S. asylum system.

The emphasis on threat control and exclusion is also “baked in” to the U.S. system in many ways. For example, the expedited removal process in U.S. law treats all border arrivals as immediately deportable unless they claim a fear of return to their home countries and then allows access to asylum only for those who pass a screening interview.75 Similarly, those who pass this screening must still make their claim to asylum in adversarial removal proceedings before the non-specialized immigration courts rather than before a refuge determination corps.76 All those who seek asylum after an encounter with immigration authorities and are not subjected to expedited removal, whether they turn themselves in at the border to seek asylum or are apprehended within the United States, must present their claim in these adversarial immigration court proceedings.77 To be clear, the asylum claim is made within “removal” proceedings where asylum is offered as a defense to removal rather than as a freestanding claim for protection.78

This underpinning framework of suspicion must be considered to address more fully the policies adopted to blockade the border during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some theorize that the existence of generous asylum policies in place for those who reach a national territory inspire restrictions that seek to prevent asylum seekers from ever reaching that territory.79 The “remote control” or exclusionary policies are seen to put up a shell that protects a soft center. They function as a way of ensuring that a nation may appear to grant asylum rights broadly but only offer those rights in practice to a scarce few. In the United States, the opposite may be true. The stinginess and restrictiveness of the U.S. asylum process at its core may be seen to have emanated outward to the border and beyond. The limits and restrictions on recognition of asylum which were formulated within the United States have injected an ethos of exclusion and suspicion into the asylum process. In turn, the exclusionary approach that begins within the United States allows for increasingly aggressive measures at the border and beyond. The buildup of restrictions on asylum within the United States, constructed on a foundation of exclusion and threat control, may be seen to have created the base for the blockade at the border. The very nature of the underlying system must therefore be addressed to ensure that the blockade at the border does not become permanent.

Conclusion

Actions taken by the Trump Administration invoking the COVID-19 pandemic effectuate a level of exclusion of asylum seekers at the border that would have been hard to imagine even recently. The barricade at the border did not appear out of thin air, however, but is instead an extreme version of a U.S. asylum system that has been focused on security and has treated exclusion as the norm and asylum protection as the rare exception. As one commentator noted: “We codify the nation's fears into law, yet we delegitimize the fears of our neighbors, the fears of refugees and asylum seekers—many of whom are fleeing actual, immediate, duck-for-cover, jackboots-kicking-at-your-door, the-roof-is-collapsing fear (Washington, 2020).”

Perhaps the need to address the border blockade will allow for a rethinking of the U.S. asylum system. A deeper look would make clear that the security and fraud focus is a poor match with the realities at the border. In the realization, it may be possible to break down the barricade and build a system that prioritizes the need to process and evaluate asylum claims rather than exclude. Such a system would almost certainly be more efficient and more humane.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Part of a COVID-19 Research Topic. This article is fully waived.

Footnotes

1. ^See 8 U.S.C. 1158(a)(1); INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1987); U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Refugees and Asylum, Available online at: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-and-asylum (accessed November 4, 2020).

2. ^See, e.g., U.S. Border Patrol Monthly Apprehensions, Available online at: https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2020-Jan/U.S.%20Border%20Patrol%20Monthly%20Apprehensions%20%28FY%202000%20-%20FY%202019%29_1.pdf (accessed December 6, 2020).

3. ^See, e.g., GAO, Unaccompanied Children: Agency Efforts to Reunify Children Separated from Parents at the Border (Oct. 2018), Available online at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694963.pdf; IACHR, IACHR Grants Precautionary Measure to Protect Separated Migrant Children in the United States (Sept. 2018), Available online at: https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/media_center/PReleases/2018/186.asp; New York Times, ‘We Need to Take Away Children,' No Matter How Young, Justice Dept. Officials Said (Oct. 6, 2020), Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/06/us/politics/family-separation-border-immigration-jeff-sessions-rod-rosenstein.html?smid=em-share-v1 (accessed December 6, 2020).

4. ^See, e.g., U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE Detention Data, Available online at: https://www.ice.gov/detention-management; Migration Policy Institute, Trump Administration's New Indefinite Family Detention Policy: Deterrence Not Guaranteed (Sept. 26, 2018), Available online at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/trump-administration-new-indefinite-family-detention-policy; BBC, US Ruling to Expand Indefinite Detention for Some Asylum Seekers (April 17, 2019), Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-47952648; R.I.L.-R. v. Johnson, 80 F.Supp. 3d 164 (D.D.C. 2015) (establishing that family detention was unlawfully used as deterrence).

5. ^U.S. Department of Homeland Security, DHS and DOJ Issue Third-Country Asylum Rule (2019), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/07/15/dhs-and-doj-issue-third-country-asylum-rule (accessed November 4, 2020).

6. ^Al Otro Lado v. Wolf, 952 F.3d 999 (9th Cir. 2020); Human Rights First, Asylum Denied, Families Divided: Trump Administration's Illegal Third-Country Transit Ban, Available online at: https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/resource/asylum-denied-families-divided-trump-administration-s-illegal-third-country-transit-ban (accessed November 4, 2020).

7. ^27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G. 2018); Nat'l Immigrant Justice Center, Matter of A-B- and Matter of L-E-A-: Information and Resources (2020), Available online at: https://immigrantjustice.org/for-attorneys/legal-resources/topic/matter-b-and-matter-l-e-information-and-resources (accessed November 4, 2020).

8. ^See Jon Hiskey, et al., Leaving the Devil You Know: Crime Victimization, US Deterrence Policy, and the Emigration Decision in Central America, 53 Latin American Research Review 429–447 (2018), Available online at: http://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147; Congressional Research Service, Asylum and Credible Fear Issues in U.S. Immigration Policy (June 29, 2011) (“conditions in. source countries. were likely the driving force behind asylum seekers”), Available online at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R41753.pdf (accessed December 6, 2020).

9. ^U.S. Border Patrol Monthly Apprehensions, Available online at: https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2020-Jan/U.S.%20Border%20Patrol%20Monthly%20Apprehensions%20%28FY%202000%20-%20FY%202019%29_1.pdf; CBP, Claims of Fear, Available online at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/claims-fear (accessed December 6, 2020).

10. ^Leutert, S. (2020). Metering Update, Available online at: https://www.strausscenter.org/campi-publications/ (accessed November 4, 2020).

11. ^DHS, Migrant Protection Protocols (2019), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/01/24/migrant-protection-protocols (accessed November 4, 2020).

12. ^See 84 Fed. Reg. 63994; Americas Society/Council of the Americas, Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico (2019), Available online at: https://www.as-coa.org/articles/explainer-us-immigration-deals-northern-triangle-countries-and-mexico (accessed December 6, 2020).

13. ^See U.T. v. Barr, Complaint, 1:20-cv-00116 (D.D.C. Jan. 15, 2020), Available online at: https://www.aclu.org/legal-document/complaint-ut-v-barr (accessed December 6, 2020).

14. ^Human Rights Watch and Refugees International, Deportation With a Layover 6 (2020), Available online at: https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2020/5/8/deportation-with-a-layover-failure-of-protection-under-the-us-guatemala-asylum-cooperative-agreement (accessed December 6, 2020).

15. ^L.A. Times, Guatemala Turns Tables, Blocking U.S. Deportations Because of Coronavirus (March17, 2020), Available online at: https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-03-17/guatemala-close-borders-to-americans-trumps-deportation-flights (accessed December 6, 2020).

16. ^8 U.S.C. 1158(a)(1); U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Refugees and Asylum, Available online at: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-and-asylum (accessed December 6, 2020).

17. ^The blockade is not a physical one in the sense of a wall. As such, most asylum seekers blocked at the border do spend a period of hours, days or even weeks on U.S. territory at the border while they are processed back out of U.S. territory. However, the situation under current policies is unique in that they are not even detained under U.S. detention laws but instead are subject to processing for immediate departure with almost no access to proceedings of any kind to challenge their removal from the territory.

18. ^USCIS, Semi-Monthly Credible Fear and Reasonable Fear Receipts and Decisions by Outcome Type: July 1, 2019 to July 15, 2020, Available online at: https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-and-studies/semi-monthly-credible-fear-and-reasonable-fear-receipts-and-decisions (accessed November 4, 2020).

19. ^USCIS, Semi-Monthly Credible Fear and Reasonable Fear Receipts and Decisions by Outcome Type, Available online at: https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-and-studies/semi-monthly-credible-fear-and-reasonable-fear-receipts-and-decisions (accessed December 6, 2020).

20. ^85 Fed. Reg. 41201; Bipartisan Policy Center, Proposed DHS and DOJ Rule Seeks to Further Restrict Asylum Access Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020), Available online at: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/proposed-dhs-and-doj-rule-seeks-to-further-restrict-asylum-access-beyond-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed December 6, 2020).

21. ^The safe third country agreements with Central American countries would also constitute territorial exclusion measures, but they are not functioning during the pandemic. Metering practices also fall within this category and continue to be used to some degree even during the pandemic, but their place in the blockade at the border is relatively minor.

22. ^DHS, Secretary Kirstjen M. Nielsen Announces Historic Action to Confront Illegal Immigration (2018), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2018/12/20/secretary-nielsen-announces-historic-action-confront-illegal-immigration-hereinafter-Nielsen~Announcement (accessed November 4, 2020).

23. ^See Human Rights First, Delivered to Danger: Illegal Remain in Mexico Policy Imperils Asylum Seekers' Lives and Denies Due Process 21–22 (2019), Available online at: https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/Delivered-to-Danger-August-2019%20.pdf (accessed November 4, 2020).

24. ^DHS, DHS Expands MPP To Brazilian Nationals (2020), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/01/29/dhs-expands-mpp-brazilian-nationals (accessed November 4, 2020).

25. ^DHS, Migrant Protection Protocols (Jan. 24, 2019), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/01/24/migrant-protection-protocols (accessed December 6, 2020).

26. ^White House, Statement from the President Regarding Emergency Measures to Address the Border Crisis (May 30, 2019), Available online at: www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-regarding-emergency-measures-address-border-crisis/; Donald Trump (@realDonaldTrump) TWITTER (Jun 7,2019, 5:31PM), Available online at: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1137155056044826626 (accessed December 6, 2020).

27. ^8 U.S.C. 1225 (b)(2)(C).

28. ^See Innovation Law Lab v. McAleenan, 924 F.3d 503, 506 (9th Cir. 2019) (per curiam) (stays of the order invalidating MPP resulted in the ongoing operation of MPP pending a decision on the merits as to its legality).

29. ^See TRAC Immigration, Details on MPP (Remain in Mexico) Deportation Proceedings (2020), Available online at: https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/mpp/ (accessed November 4, 2020).

30. ^Human Rights First, Delivered to Danger, supra note 21.

31. ^Harvard Global Health Initiative and Boston College School of Social Work. A Population in Peril: A Health Crisis Among Asylum Seekers on the Northern Border of Mexico (2020), Available online at: https://globalhealth.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/A_Population_in_Peril.pdf (accessed November 4, 2020).

32. ^Newsweek, Asylum Seekers Trapped at Border Camp Face Coronavirus, Cartels and Storms but Still no Help from US (July 27, 2020), Available online at: https://www.newsweek.com/asylum-seekers-trapped-border-camp-face-coronavirus-cartels-stormsbut-still-no-help-u-s-1520702; Doctors without Borders, U.S. Must Include Asylum Seekers in COVID-19 Response Rather than Shut Border (March 27, 2020), Available online at: https://www.msf.org/us-must-include-asylum-seekers-covid-19-response; The New York Times Opinion, The Impending Mass Grave Across the Border from Texas (April 12, 2020) (describing the lack of proper hygiene conditions and the lack of medical attention for those awaiting MPP proceedings in the crowded refugee encampment in Matamoros, Mexico), Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/12/opinion/matamoros-migrants-coronavirus.html (accessed December 6, 2020).

33. ^Request for Precautionary Measures to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (June 17, 2020), Available online at: https://law.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2020/02/2020-IC-Request-for-PM-MPP.pdf (describing case of Honduran family that had been kidnapped in Mexico, then separated by US border officials and returned to Mexico, where the decision was made to abandon the U.S. asylum claim and return to Honduras).

34. ^TRAC, Details on MPP (Remain in México) Deportation Proceedings (March 2020) (the percentage of persons receiving “relief” as compared to the percentage receiving orders of deportation).

35. ^CBP, MPP Guiding Principles (2019), Available online at: https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Jan/MPP%20Guiding%20Principles%201-28-19.pdf (accessed November 4, 2020).

36. ^Joint DHS/EOIR Statement on the Rescheduling of MPP Hearings (May 10, 2020), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/05/10/joint-dhseoir-statement-rescheduling-mpp-hearings (accessed December 6, 2020).

37. ^DOJ, Department of Justice and Department of Homeland Security Announce Plan to Restart MPP Hearings (2020), Available online at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-and-department-homeland-security-announce-plan-restart-mpp-hearings (accessed November 4, 2020).

38. ^CBP, Migrant Protection Protocols, Available online at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/migrant-protection-protocols (showing more than two hundred new enrollments in MPP in June 2020) (accessed November 4, 2020).

39. ^Migrant Protection Protocols, supra note 10 (those found by the immigration courts to have meritorious claims will be allowed to enter the United States).

40. ^See Human Rights First, Delivered to Danger, supra note 21.

41. ^85 Fed. Reg. 17060; Associated Press, Pence Ordered Borders Closed after CDC Experts Refused (2020), Available online at: https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-pandemics-public-health-new-york-health-4ef0c6c5263815a26f8aa17f6ea490ae (accessed December 6, 2020).

42. ^DHS, Fact Sheet: DHS Measures on the Border to Limit the Further Spread of Coronavirus (2020), Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/03/23/fact-sheet-dhs-measures-border-limit-further-spread-coronavirus (accessed November 4, 2020).

43. ^85 Fed. Reg. 31503 (May 26, 2020).

44. ^8 U.S.C. 1158, 1225.

45. ^8 U.S.C. 1232.

46. ^CBS News, U.S. to Rapidly Turn Away Migrants, including those Seeking Asylum, Over Coronavirus (March 21, 2020), Available online at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-to-turn-way-migrants-including-those-seeking-asylum-without-delay-over-coronavirus/; see also Joint Statement on US-Mexico Joint Initiative to Combat the COVID-19 Pandemic, Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/03/20/joint-statement-us-mexico-joint-initiative-combat-covid-19-pandemic (accessed December 6, 2020).

47. ^LA Times, Central America Fears Trump Could Deport the Coronavirus (March 29, 2020), Available online at https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-03-29/trump-deportations-guatemala-coronavirus (accessed December 6, 2020).

48. ^CBP, Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions, Available online at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics (accessed December 6, 2020).

49. ^CBS News, U.S. Policy of Expelling Migrant Children without an Asylum Interview Challenged in Class-Action Lawsuit (2020), Available online at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/lawsuit-seeks-to-halt-u-s-policy-of-expelling-migrant-children-without-an-asylum-interview/ (accessed November 4, 2020).

50. ^ABC News, AP Exclusive: Migrant Kids Held in US Hotels, Then Expelled (2020), Available online at: https://abcnews.go.com/Business/wireStory/ap-exclusive-migrant-kids-held-us-hotels-expelled-71918837 (accessed November 4, 2020).

51. ^Associated Press, Pence Ordered Borders Closed after CDC Experts Refused, supra note 38.

52. ^See UNHCR, Practical Recommendations and Good Practice to Address Protection Concerns in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic 2 (2020), Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/cy/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2020/04/Practical-Recommendations-and-Good-Practice-to-Address-Protection-Concerns-in-the-COVID-19-Context-April-2020.pdf (accessed December 6, 2020).

53. ^85 Fed. Reg. 31503, 31507 (May 26, 2020).

54. ^85 Fed. Reg. 17060, 17064.

55. ^85 Fed. Reg. 06253 (March 24, 2020).

56. ^ProPublica, ICE is Making Sure Migrant Kids Don't Have COVID-19—Then Expelling Them to “Prevent the Spread” of COVID-19 (2020), Available online at: https://www.propublica.org/article/ice-is-making-sure-migrant-kids-dont-have-covid-19-then-expelling-them-to-prevent-the-spread-of-covid-19 (accessed November 4, 2020).

57. ^World Health Organization, Updated WHO Recommendations for International Traffic in Relation to COVID-19 Outbreak (Feb. 29, 2020), Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/updated-who-recommendations-for-international-traffic-in-relation-to-covid-19-outbreak; see also International Health Regulations, art. 2 (2005) (providing standards for governments to follow in order to “avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade” while addressing international spread of disease).

58. ^Associated Press, Pence Ordered Borders Closed after CDC Experts Refused, supra note 38.

59. ^Letter to CDC Director Signed by Medical Experts (May 18, 2020), Available online at: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/public-health-experts-urge-us-officials-withdraw-order-enabling-mass-expulsion-asylum-seekers (accessed December 6, 2020).

60. ^See 8 U.S.C. 1158(a)(1); U.N. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, 189 U.N.T.S. 150 [hereinafter Refugee Convention], as extended by the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 606 U.N.T.S. 267 [hereinafter Refugee Protocol]. Entered into force for the United States, Nov. 1, 1968, through accession to the Refugee Protocol; Refugee Act of 1980, Public Law 96-212 (adopted March 17, 1980); UNHCR, Key Legal Considerations on Access to Territory for Persons in Need of International Protection in the Context of the COVID-19 Response (March 16, 2020), Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5e7132834.html (accessed December 6, 2020).

61. ^See, e.g., CBS News, Federal Judge Skeptical of Trump Order Used to Expel Migrants at Border (June 25, 2020), Available online at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/federal-judge-trump-order-migrant-expulsions-policy-aclu/; Innovation Law Lab v. Wolf , 951 F.3d 1073 (9th Cir. 2020).

62. ^See, e.g., Innovation Law Lab v. Wolf , 140 S.Ct. 1564 (2020); NPR, U.S. Supreme Court Allows 'Remain In Mexico' Program To Continue (March 11, 2020), Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2020/03/11/814582798/u-s-supreme-court-allows-remain-in-mexico-program-to-continue (accessed December 6, 2020).

63. ^See also Department of Homeland Security v. Thuraissigiam, 140 S.Ct. 1959 (2020).

64. ^UNHCR, Key Legal Considerations, supra note 55, at 1.

65. ^Joint Guidance Note on the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Human Rights of Migrants by the UN Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants (26 May 2020), Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/TB/COVID19/External_TB_statements_COVID19.pdf (accessed December 6, 2020).

66. ^IACHR, IACHR Concerned About Restrictions of the Rights of Migrants and Refugees in the United States During COVID-19 Pandemic (2020), Available online at: https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/media_center/PReleases/2020/179.asp (accessed November 4, 2020).

67. ^See Communication from IACHR (on file with the author).

68. ^See, e.g., Ilias and Ahmed v. Hungary, E.Ct.H.R. (2019) (permitting deprivation of liberty at the border but requiring adequate processes to ensure access to asylum protection before returning an asylum seeker to a third country for processing).

69. ^See, e.g., National Council 118 – Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Vote of No Confidence in Director John Morton (June 25, 2010), Available online at: http://iceunion.org/download/259-259-vote-no-confidence.pdf (union vote of no confidence in ICE leadership where officers asked to make prosecutorial discretion decisions and improve detention conditions).

70. ^Migrant Protection Protocols, Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/01/24/migrant-protection-protocols (accessed December 6, 2020).

71. ^See United States Holocaust Museum, Holocaust Encyclopedia: Voyage of the St. Louis, Available online at: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/voyage-of-the-st-louis (accessed December 6, 2020).

72. ^See Smithsonian Magazine, The U.S. Government Turned Away Thousands of Jewish Refugees, Fearing That They Were Nazi Spies (2015), Available online at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/us-government-turned-away-thousands-jewish-refugees-fearing-they-were-nazi-spies-180957324/?no-ist (accessed November 4, 2020).

73. ^U.N. Refugee Convention.

74. ^Edward M. Kennedy, Refugee Act of 1980, 15 International Migration Review 141 (1981).

75. ^8 U.S.C. 1225; American Immigration Council, A Primer on Expedited Removal (2019), Available online at: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/primer-expedited-removal (accessed November 4, 2020).

76. ^8 U.S.C. 1229; 8 C.F.R. 208.30(f); American Bar Association, Reforming the Immigration System 2:3-2:33. (2019), Available online at: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/commission_on_immigration/2019_reforming_the_immigration_system_volume_2.pdf (accessed November 4, 2020).

77. ^8 U.S.C. 1229.

78. ^An “affirmative” asylum process outside of Immigration Court removal proceedings does exist in the United States but it is only applicable to those who arrive in the United States and apply affirmatively before any apprehension or other encounter with immigration enforcement authorities.

79. ^Fitzgerald, supra, at 6-14, 252-54.

References

Eagly, I., and Shafer, S. (2020). The Continued Detention of Migrants in U.S. Detention Centers During the COVID Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2020/07/continued (accessed November 4, 2020).

Goodman, C. (2016). Between Foreign Policy, Politics, and the Law: The United States Refugee Crises of 1980. Available online at: https://www.humanityinaction.org/knowledge_detail/between-foreign-policy-politics-and-the-law-the-united-states-refugee-crises-of-1980/ (accessed November 4, 2020).

Washington, J. (2020). The Long, Winding, and Painful Story of Asylum. The Nation. Available online at: https://www.thenation.com/article/society/asylum-history-united-states/ (accessed November 4, 2020).

Keywords: asylum, border, migration, COVID-19, refugee, migrant protection protocol, expulsions

Citation: Gilman D (2020) Barricading the Border: COVID-19 and the Exclusion of Asylum Seekers at the U.S. Southern Border. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2:595814. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2020.595814

Received: 17 August 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020;

Published: 21 December 2020.

Edited by:

Jaya Ramji-Nogales, Temple University, United StatesReviewed by:

Susan Gzesh, University of Chicago, United StatesSusan Martin, Georgetown University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Gilman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denise Gilman, ZGdpbG1hbiYjeDAwMDQwO2xhdy51dGV4YXMuZWR1

Denise Gilman

Denise Gilman